Institutions, Politics, and Realignment

How the "Trump phenomenon" is much bigger than just President Trump

Art often explains better than prose. And I believe our current political divide is best understood through the lens of—believe it or not—the October 2016 version of Saturday Night Live’s “Black Jeopardy.” In this hilarious but deeply insightful sketch, Tom Hanks portrays “Doug,” a MAGA-hat wearing (and very white) rural American man. As the sketch progresses, Doug shocks the host and contestants of Black Jeopardy by consistently having the “correct” responses. Doug convincingly illustrates the deep commonalities that he—representing the rural white underclass—has with the contestants from the urban black underclass. Most fundamentally, they share a distrust of institutions—the questions cover violations of privacy, election fixing, suspicion of the government, the informal economy, and a preference for lottery scratch cards, rather than contributing to a 401K.[i]

This sketch prepares us, in a way no essay could, for the realignment we are seeing unfold in American politics. The political class has been in a mad scramble, since November of 2016, to explain what the “Trump phenomenon” means and how it came about. The American body politic is in a major partisan realignment, with both parties trading significant blocks of voters at the ballot box. I believe the best way to understand this realignment is by observing how Americans—individually and in groups—think about their relationships to major American institutions. While this model has some limitations, and legacy attachments are often relevant, it seems to have great explanatory power.

Simply put, the Democrats have become the party of the institutions. Meanwhile, the Republicans now exist in a realm somewhere between suspicion of, and outright hostility to, the institutions. I believe this simple litmus test is our most salient political divide. That institutions are key is an important nuance. Other observers have nominated education or class, and these are obviously closely correlated with one’s connection to the institutions and can therefore be useful ways to think about the changing political scene. But these variables are proxies for this institutional relationship and fail to explain some phenomena.

By “the institutions” I mean the main power centers in American society and its economy. So media and academia are near the top, but followed by the various branches of executive power that have frequent interaction—federal police agencies, the IRS, the NIH, CPS, the intelligence agencies. Large firms also count as “institutions,”—“Big Law”, tech firms, big pharma, big agriculture, finance and banks and the “military industrial complex” (though of course this last still has major Republican ties). The military and law enforcement are the exceptions (though not totally exempt) that prove this rule.

There are two interrelated but clearly distinct questions about the institutions that will drive your partisan alignment. First, are these institutions working for you? Are you benefiting from the operation of these institutions, in a way you can see and feel? And second, do you trust the institutions, independent of whether you are getting a good deal from them?[ii]

It is at least theoretically possible to parse all these. So for example, a military general or admiral almost certainly trusts the institution in which he has ascended, and (not coincidentally) he is doing quite well in it. The inverse is equally easy to picture. An unemployed, lower class homeless woman is not being well served by any institution, and has no trust in “the system” writ large. For that matter, looping back to the military, you could also picture a one-term enlistee who fell into a unit with bad leadership and (therefore) poor morale who would therefore have no confidence in the institution he or she left behind.

Those who are conflicted are slightly more difficult to picture and we could attempt to.[iii] But those who believe despite not doing well, or who are doing well but don’t believe, will be small sets, so we can skip over them for simplicity’s sake. So to restate, if the institutions are benefiting you and you believe in them, you are likely a Democrat. If the institutions are not serving you well, and therefore you have lost faith in them, you are likely a Republican.

For those under 40, it is difficult to communicate just how dramatic a shift this is in American Politics. If we were to take 1980, for example, as our start point, virtually all the institutions would be aligned with the Republicans—academia, unions, and the pieces of government Reagan would describe as the “welfare state” notably excepted. But to be part of the elite mainstream social fabric was, for the most part, to be a Republican. It was “morning in America.”

Conversely, to be countercultural, to have distrust of established institutions, was to be of the left, to be a Democrat. After all, it was the left that wanted to “Rage Against the Machine.”

But this is simply not the case anymore and realignment appears to be very visibly underway. Just to do one data point, let us look at Johnson County, Kansas, the county outside of Kansas City that contains the professional elite of eastern Kansas. In 1980, it voted overwhelmingly for Ronald Reagan, 63% for Reagan to only 26.8 for incumbent Democratic President Jimmy Carter. In 2020, however, the county voted for Joe Biden, albeit not overwhelmingly (though perhaps overwhelming for Kansas), but with a clear shift, 52.7% to only 44.5% for Donald Trump. Realignments take time and there are lags. The same voters who were 40 in 1980 and voted for Reagan turned 80 in 2020, and are unlikely to shift partisan alignment at that point in their lives. But their younger counterparts in more junior cohorts, have likely shifted. The 40 year old who holds in 2020 the same job that the Reagan voter did in 1980, was likely a Biden voter. The partisan position of those with loyalty to the institutions has largely reversed itself.

So the professional class—those in the institutions and with loyalty to the institutions—has moved from being a Republican voting demographic to a Democratic one. And empirical data clearly supports this, as above. But the flip side of the movement by the professional class is the equal and opposite reaction from the working classes. Ruy Texiera—a Democratic party strategist—has been warning his fellow partisans for some time now about the dangers of the Democrats becoming “a Brahmin Left party, beloved by the educated but increasingly viewed with suspicion by the working classes of all races.”

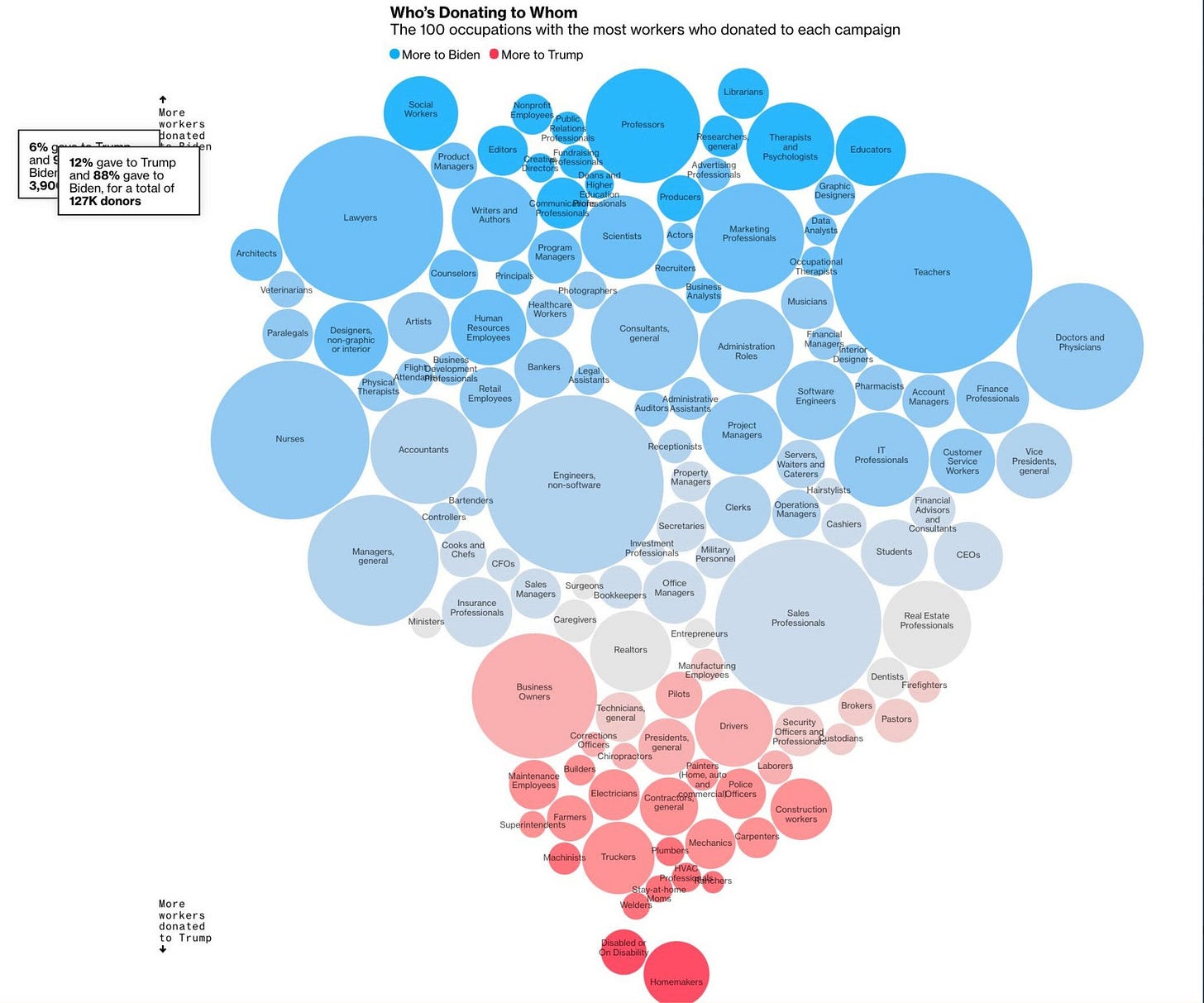

I encountered the following graph when it was originally posted by the pseudonymous “Trace Woodgrain” on his Substack. The usual caveats apply. This is one single event in time—the 2020 Presidential election—and the graph uses a proxy variable—monetary contributions to the Presidential campaign—as an indicator of support.

Using this graph as a proxy, the data seems to support the thesis that the institutions have become Democratic strongholds. In more or less ranked order, the Biden contributions came from professors, social workers, therapists, lawyers, librarians, deans, scientists, teachers, doctors, pharmacists, designers, bankers, IT professionals, finance professionals, nurses, accountants, engineers, CEOs.

In other words, the members and representatives of the institutions.

Contrast this with the contributors to the Trump campaign. Housewives, the disabled, carpenters, electricians, truckers, mechanics, plumbers, builders, police, drivers, construction and maintenance workers. In the main (the police perhaps being the exception that proves the rule), a group largely outside what we view as mainstream institutions. These are tradesmen/women, manual laborers, and hourly workers.

It would be an oversimplication to define this as the upper middle class versus the lower middle class, but only slightly. If thinking in terms of pure income, then doubtless there are plumbers and electricians whose net earnings exceed those of some therapists, for example. But in the main, we see a group of salaried professionals arrayed against a similar grouping of hourly blue collar workers.

And while it is dangerous to extrapolate from your data, I think it is relatively safe to believe that underneath the group of fairly well-to-do tradesmen who have the funds to contribute to a political campaign exists a camp of more marginalized workers. Those who no longer have disposable income for political campaigns will be the least well-served by the institutions and therefore will be part of this realignment.

There are still a small number of blue-collar professions where a robust middle class lifestyle is possible. At the high end, an offshore oil and gas supervisor making over $200K annually with his home in low cost-of-living Mississippi, Louisiana, or East Texas is definitely living a top 1% lifestyle. While perhaps not at that end, UAW workers at the “Big Three” automakers, union electricians, experienced HVAC repairmen, and other specialized tradesmen may crest $100K annual compensation. But these jobs are far from the average and often hard to acquire. Far more typical is work at a small, family-owned, non-union assembly plant or in services or retail at just above minimum wage. This has meant deep economic insecurity, inability to provide, loss of housing, and a continual sense of living on the edge for many families without the education to enter the middle class. Frontline’s recent episode “Two American Families” powerfully illustrates what this has meant for these laboring classes, black and white.

The industries in which a respectable middle-class salary is achievable has also shrunk considerably. If we look back to 1980 as a starting point, a high-school graduate could support a family on a single salary in a wide variety of industries: timber, steel, family farming, mining, fishing. But the timber wars (with both Canadians and conservationists), the farm crisis, the steel crisis, the collapse of the fisheries, and coal decline left a very narrow range of possibilities for the former blue collar middle class.

So returning to the institutions as the fundamental divide, those in the group moving into the realigning Republican party tend not to be a member of an institution, and is therefore suspicious of the institutions. And in fact, that suspicion may grow to the point where the value and orientation of the institutions itself is questioned. This isn’t irrational. Why should one give trust and loyalty to institutions that do nothing—at least visibly—for you? Or worse yet, distort natural forces and keep you poor and marginalized?

Here the theory starts to explain some otherwise curious facts. Why the new Right questions the media (hint: it’s an institution). Why the new Right questions the utility of the professional government bureaucracy (it’s an institution, and more critically, one filled with Democratic partisans that will resist the policies of the new Right). Why the new Right is hostile to established higher education. Why there is deep suspicion of the financial system. Of the judicial establishment. The new Right that is moving into the Republican party—often displacing long-established demographics—has no tie to these institutions (save perhaps hostile ones—court summons, rejection letters, and bill collectors) and therefore carries deep suspicion of their motives. Further, their elites—while by definition generally well-educated and with financial resources—will tend to be outside the institutions, having made comfortable lives in a relatively independent manner. Think small business owners, heirs of family car dealerships, ranchers (and yes, commercial building developers). And given the data above, demonstrating that those inside the institutions are uniformly opposed to the political interests of those outside the institutions (at least as they understand them), then the suspicion of the institutions is not irrational.

Understanding the role of institutions as a fundamental divide explains otherwise curious happenings. The movement of the Cheneys (both former vice president Dick and daughter/former Congresswoman Liz) from the Republicans to the Democrats is on the surface curious. But when you think of the divide between the institutions, it makes much more sense. The Cheneys are just as much products of the institutions as are (e.g.) the Clintons. So of course they now belong in the same party, differing positions in the 90s and 00s notwithstanding. Likewise other prominent defectors. The closer one’s interests to the major institutions, the more one shares their views, their interests, their priorities. Again, exceptions abound. Politics is not an exact science. But thinking about this division in this way does seem to add clarity to the current political scene. And to loop back to culture for a moment, this helps understand why the folk-rock anthem “Fast Car,” that when first recorded in 1988 was clearly associated with the black urban underclass, would experience a revival in 2023 as a country ballad directed at the white rural underclass. Same isolation and despair; different political refuge.

The obvious question this viewpoint raises is the relationship of the trend to the emergence of President Donald Trump as the spokesman for the realigning party. Put simply, how much did President Trump cause this new bifurcation, or how much did this bifurcation cause Trump?

I suspect the answer is somewhere in-between, that President Trump’s harnessing of this divide accelerated it. This political division pre-dates the emergence of the Trump phenomenon, I believe. This is particularly true if you believe 2008 to be the polarizing moment. But President Trump’s genius as a political entrepreneur was to see this emerging divide in a way no other figure did—save perhaps Bernie Sanders, who was less well-positioned to exploit it. President Trump recognized and earned the loyalty—often fanatical loyalty—of this otherwise isolated demographic. Further, he recognized, whether consciously or not, that this demographic was likely to grow in size as a voting block as income inequality accelerated. This looked—and looks—like a long-term winning strategy.

That a New York property developer would emerge as the spokesman for this disempowered class is at one level bewildering, but at another fully understandable. Peasant revolts are usually led by counter-elites. And while President Trump is of power and money, he is not from an institution and has usually stood in opposition to them. Land developers are often seen as disreputable. Thought of this way, this emergence is very understandable, particularly given the former President’s ability to speak to the masses in their own dialect so to speak, perfected in reality television, but first developed on the margins of professional wrestling and on construction sites throughout New York and New Jersey.

The addition of Robert F Kennedy, Jr, and Tulsi Gabbard into Donald Trump’s orbit fits nearly with this theory (likewise Vivek and Elon). Each of these figures is also defined by opposition to mainstream institutions—food and pharma in the former case, the defense industrial complex and transgenderism in the second—and by their positioning of themselves as change agents.

Accepting this viewpoint also explains diverging opinions in the two parties on the “threat to Democracy.” It has become a trope of those in the institutions that “Donald Trump is a threat to our democracy.” By this they mean, I think, that Trump is a threat to the institutions, which they see as a bulwark of democracy.

However, for the new Right, the threat to democracy comes from the institutions themselves, which are the problem. So President Trump’s defenders would turn his opponent’s rhetoric on its head and reply to Democrats that while Trump is indeed a threat to “their democracy,” the one that serves the interests of Democratic partisans in the institutions, what is in the larger good for democracy is a round of creative destruction of these same institutions. In this view, the institutions that those inside them most value require fundamental reform, from their mid-20th century orientation to one that serves the early 21st. Again, this thought is anathema to those whom the current institutional arrangements are conveniently serving.[iv]

If we were to identify one moment when the old order really cascaded into the new, the 2008 financial crisis would have to be it. The 2008 financial bailout, which gave out billions of dollars while holding no one responsible, had the approval of not only the sitting President, George W. Bush, but also that of both candidates to succeed him, John McCain and Barrack Obama. In Angelo Codevilla’s telling in his 2010 The Ruling Class, “When this majority [of 80% disapproval of the proposed policy] discovered that virtually no one with a national voice or in a position of power in either party would take their objections seriously…they realized that America’s rulers had become a self-contained, self-referential class.” Finding that those responsible for the pain the 2008 crisis inflicted on the working classes would not only not face criminal charges and prison, but would retain their taxpayer-underwritten bonuses, was—I suspect—a seminal moment for many. Ten million American families lost their homes to foreclosure during the subprime crisis. While now extrapolating, that this anger would drive a movement to look for a party that equally excluded the institutions that backed the Bushes, McCains and Obamas is hardly a huge leap.

Then packed on top of 2008 has come a series of events, or at least gradual reorientations, that have changed the view of the institutions. While the version in most heads is probably not literary, there is an impressive literature from mainstream publishers that has likely “trickled down.” Think of Chris Van Tulleken on the processed food industry, or Chris Leonard on the role of the Federal Reserve in increasing income inequality, or Gretchen Morgenson on the “plunderers” of private equity, or Patrick Radden Keefe on the “Empire of Pain” created by the Sacklers and Purdue Pharma. While ironically these authors (who are mostly institutionalists themselves!) may be perfectly happy with most other institutions, and just pointing out an abuse in one, when taken as a whole, it can be read as a critique of the entire universe of institutions.

Then in the more popular sphere, think of the tarnishing of academia by several rounds of plagiarism scandals among fairly major figures, beginning with the former Harvard President. For the intelligence community, think of the 51 former members who signed a letter, organized by the Biden campaign, claiming that the Hunter Biden laptop story “makes us deeply suspicious that the Russian government played a significant role.” On the intersection of Covid and journalism, think of headlines such as “Senator Tom Cotton Repeats Fringe Theory of Coronavirus Origins,” when the lab-leak theory he was promoting is now generally seen as the most probable explanation (though we will likely never know).

All these incidents, calling deep doubt on the functioning of mainstream institutions are themselves rather, well, mainstream. This is not lizard people, Q-Anon, or a global conspiracy of Satanists or Freemasons or Opus Dei or Jews or the Trilateral Commission or whomever. These are instead fairly straightforward cases that call into question whether there are fundamental issues at the roots of many major institutions. These critiques, taken together, then question the functioning of the larger system of institutions as a whole.

If we accept this vision of the two parties becoming reoriented around institutions, a few observations emerge. First, this new orientation will create new islands of political homelessness. On the left, what happens to the long-term fraction of the left that is inherently anti-institutional? Think of publications such as Dissent and The Nation. These small outlets often carry powerful critiques of the institutions (see, e.g. The Nation’s recent expose on the collusion of “Big Agriculture” and powerful NGOs to force GMO seeds on the global south). But while these organs have always been minority voices in the Democratic coalition, it is hard to see them not becoming further and further marginalized over time as the counterculture becomes more and more a right-leaning phenomenon.

Similarly, on the right, what happens to those who are fully supportive of the current institutional arrangements? We could call this fraction “Nikki Haley Republicans.” What of those who view themselves as deeply conservative, but are deeply embedded in the institutional structure and doing quite nicely in them, if perhaps having to regularly self-censor. This fraction may contain a sizeable portion of what we might think of as the “professional right,” the think tanks that have generally served as the institutionalized opposition—think of the American Enterprise Institute, the Hoover Institution, the Heritage Foundation, the Acton Institute. None of these can be plausibly viewed as hostile to current institutional arrangements. Where do they fit along this new political cleavage? (hint: the endorsement of Kamala Harris by many individuals in these institutions is probably a good indicator)

Second, what is the positive agenda of the new Right? What they are against is obvious—the current institutional arrangements. But what are they for? One can see this question playing out in the coalition surrounding itself around Donald Trump. Aside from much stronger enforcement of borders and immigration policies, what a Trump administration will do is unclear. There are persons with deeply incompatible policies who are equally close to the Trump inner circle. Now granted, this is a post-election question, and it is in no one’s interest to highlight tensions in their coalition before coming to power.

There are two areas in which one can see the battle lines already forming, though there will doubtless be others. In the National Security arena, both the remnants of the “NeoCons”—proponents of robust use of US military force to change dynamics abroad—and the “restrainers”—those who believe that the United States would be better served by reducing its overseas military footprint and relying more on diplomacy and economics as primary tools—have proponents in very good standing with President Trump. It is conceivable that either, or both, could have a major role in filling the key positions of the national security state, though a more moderate middle path remains the most probable.

Similarly, in the economic arena, while proponents of industrial policy—exemplified by President Trump’s endorsement of tariffs to protect US industry—seem to have the upper hand, there are prominent “free traders”—those who believe that government intervention in the economy should be minimal to non-existent—also have representatives in the Trump camp.

In both cases, while there is a favored outcome, the minority voices are quite empowered and numerous, and the end policy is underdetermined. But the new Right seems quite determined to represent the policy preferences of a large number of Americans who resent elite consensus on both economics and foreign affairs against the “legacy” elements inside the party who represent more mainstream and traditional views on economics and foreign affairs.

Third, thoughts of formerly mainstream Republicans “reclaiming” their party are—charitably—unlikely. These forces realigning the country, while associated with President Trump, exist independently of him. While no political force is forever, this one shows no signs of dissipating.

Fourth, the two parties have exchanged large voting blocks. We might say that the Republicans have—in effect—traded a smaller group of high propensity voters (educated, white suburbanites) for a larger group of low propensity voters (working class, both white and minorities). While conventional wisdom has been for years that high turnout favors the Democrats, I suspect this will be less and less true. This may have been a major factor in the failure of the expected “red wave” of 2022—as new Republican voters will be less likely to turn out in “off-cycle” elections.

Finally, wrapping back to the opening, the theme of distrust of the institutions seems to have permeated popular culture as well. One could say that television shows such as America’s Got Talent, The Voice, and X Factor are standing challenges to the legitimacy of institutions. The entire premise of these shows is that much of the best talent in America is overlooked, often away from the coastal cultural centers, and that only by casting a wide net through accessible transparent auditions open to all can the best talent be found.[v]

The breakthrough exemplar for these shows was found not in America, but in Great Britain, on the sister show “Britain’s Got Talent.” The obviously working class Susan Boyle wowed the world in 2009 with her rendition of “I Dreamed A Dream,” going “viral” with millions of views within days and making her a minor celebrity even now.

A authentically American version of the same phenomenon was seen earlier this year, when a 55-year old school janitor from Indiana, Richard Goodall, who had never before been on an airplane before flying to his audition, similarly stunned the audience with his version of “Don’t Stop Believing.” That a 55 year old janitor has this kind of talent, but never had an opportunity to have a career in music, reinforces the belief that the institutions are somewhere between incompetent and malevolent. While yes, a singing competition is hardly at the core of the system, the message it sends is both clear and powerful—and widely disseminated.

So to restate, focusing on the institutions, their breakdown, and how this has polarized the American electorate in new and novel ways is the best model around which to think of the new American electoral politics. The distrust cascades in a way that negative experiences with one institution tend to taint all institutions, particularly for those with no significant attachment to any of them.

I believe this is where we see our political realignment today, based around trust—or lack thereof—in American institutions. This is, of course, a snapshot in time. Perhaps next year the trajectory will change and the divide will take on a different form. Further, no one model can explain all human behavior. Exceptions will always abound. But today, I believe framing partisan realignment in these terms brings the greatest understanding.

[i] Technically answers, not questions, as it’s Jeopardy.

[ii] To speak in academic jargon for a moment, Sheldon Wolin maintains that “Institutional breakdown releases phenomena, so to speak, causing political behavior and events to take on something of a random quality, and destroying the customary meanings that had been part of the old political world.” It is hard to argue that our “customary meanings” have not been deeply shaken.

[iii] Think of a PhD in English or Anthropology who still has (perhaps unsympathetically) several tens of thousands of dollars of student debt, but can not find regular work in an academic institutions, and instead struggles by, “adjuncting” for just a few thousand dollars a course, well below minimum wage, given hours worked. This person is obviously not well served by the academy as an institution, and objectively speaking, one might say the academy has “done them wrong,” by having them invest in a degree with few employment prospects. And yet one guesses that this person still believes in the academy and the mission of higher education at some level. They may well still encourage their students to consider a career in the academy and attend graduate school. Despite being one of the losers in the institution they serve, they still believe.

[iv] I think proposed solutions to our political crisis by each side further cement this interpretation. The left, the Democrats, are perfectly content with the institutions. It is the Constitutional arrangements that they wish to reform—the Electoral College and composition of the Supreme Court most notably (yes—having nine justices is not mentioned in the Constitution, but is such a longstanding norm since the 18th century that it effectively is). Conversely, the Republicans, the Right, see no issue with the Constitution, but wish to reform the implementing institutions around it, most notably the federal bureaucracy. It is notable that the left considers the latter a “threat to democracy,” while having no issue with fundamental change to Constitutional arrangements.

[v] Let us not speak of the role that “Diddy Parties” may have played in who got recording contracts and who did not. Nor Harvey Weinstein’s couch for movie roles.

I wonder if any of it can be attributed to the “Google Effect” https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20220812-the-illusion-of-knowledge-that-makes-people-overconfident.

Maybe the basic premise of institutions has failed, with the grounds of professional and technical expertise being unable to withstand attack from overtly or covertly postmodern approaches.

Now partisan and ideological think tanks replacing agencies and congressional staff as the go-to source for knowledge. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/11/newt-gingrich-says-youre-welcome/570832/

And agencies are seemingly captured, at least In the popular imagination.

There’s a scene in Dopesick where an investigator confronts an FDA employee about her knowledge that a regulator took money to help the Sacklers navigate approval of their drug. The investigator asks why she didn’t tell anyone, and she essentially says it wouldn’t have mattered. Something similar in the Big Short where regulators more interested in getting a private sector job.

Does that leave institution dwellers with a little real choice of speaking out and risking their chance for advancement or even retirement?

How much of that is due to decades of attack against all government and the death of a public service ethos?

Great article, Doug. As a life-long Republican and son of a Republican myself, this helps me to understand a little better why it seems that the most vocal Pro-Trump Republicans appear to demonstrate a desire for anarchy. They clearly wish to tear down the institutions that they feel have not served them. I fear it won’t happen with peaceful and gradual reform after witnessing January 6th and the lead up to this year’s elections. There are too many in the party that are too angry and full of desire for retribution (not excluding Mr. Trump) for that to happen in a manner that is not disruptive (and potentially oppressive or even deadly) for many Americans.